Vikram Chandra wrote beautifully of the Indus Valley civilization in Red

Earth and Pouring Rain:

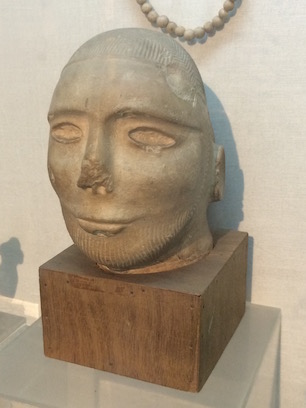

Suppose someone says, what really happened? Then say that once there were people

who built cities in the valley of the Indus, large teeming cities with broad

straight streets intersecting at ninety degrees, like a well-made grid. There

are some things that have appeared out of the drifting sands to speak

cryptically about these people; there is a statue of a sophisticated, gentle man

with contemplative, inward-looking eyes. There is a figurine of a dancing girl,

head proudly thrown back, hips carelessly and confidently thrust forward, hand

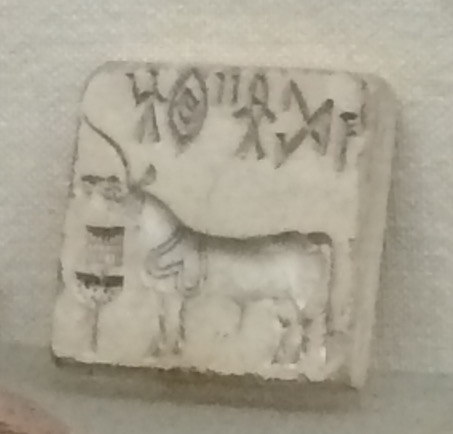

on waist, ready to break impulsively into movement. There are thousands of lines

of beautiful undecipherable writing on clay seals; on one of these seals

Pashupati sits in meditation, the supreme Yogi, the Lord of animals, the wild

king of the forest who holds the universe together with his dance, penis erect

in gathered energy. There is the figure of the bull, dewlapped and powerful,

repeated endlessly on the seals. There are the toys, the thousands of clay

animals and carts like the ones we see on country roads today. There are the

great baths, now empty; the wind shifts dust endlessly across the desert.

Where did this richness go? Is it true that a tribe riding chariots appeared out

of the western passes, filled with the uncouth strength of the steppes,

worshipping a rain-god soon to be called the Destroyer of Cities? Were there

massacres and raids and despair? Or did the river change course and leave the

long streets empty and silent? Or did the cities just grow old, very, very old,

and collapse in on themselves like a stand of dying trees? Nobody knows, but we

do know that Shiva still meditates endlessly among the awe-struck animals, that

the legends of the chariot-riding Aryans speak of old dark-skinned Asuras, who

imparted knowledge of secret sciences to chosen students, that brave adventurers

fell in love with the daughters of their enemies, the ones from before, the ones

who worshipped old gods, that the sounds of the languages of the south seem to

fit the strokes of that undecipherable writing,…

The Aryans moved west and south, clearing forests for their cattle, and Indra

the thunder-god became Indra the Destroyer of Cities. But, though cities are

often destroyed, sometimes they do not vanish, sometimes they become invisible

and invade the hearts and minds of the destroyers, who then live forever

changed.

At the National Museum, we got to see most of the works Chandra referred to in

that excerpt. I suspect he meant the Karachi carving as the

“sophisticated, gentle man”, though he may have had in mind another

wonderful head of a priest from Mohenjo-daro that we saw today. His famous

dancing girl was there, “hips carelessly and confidently thrust

forward”, and look at this elegant male torso:

|