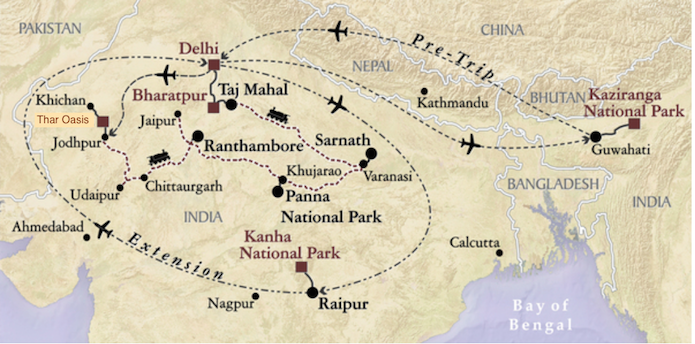

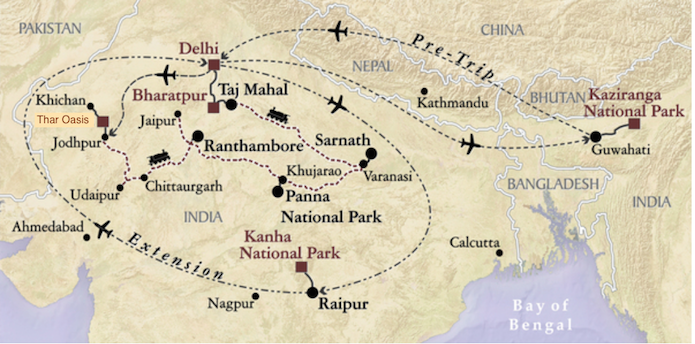

Today we drove northwest from the Thar Oasis to the village of Khichan and back

(Image courtesy of VENT)

(Click on images to enlarge)

|

Khichan is a village in the Thar Desert that has somewhat accidentally become

an internationally important birding site. This began some years ago when

villagers took to putting out grain for the Demoiselle Cranes who were wintering

nearby. That attracted more cranes and then even more, until now around 10,000

cranes come to be fed each day during the winter, and they eat something like

900 kilos of millet each day. The villagers have had to build a large walled

compound in which to feed the birds. Inevitably, this gathering of cranes has

attracted many visitors to the village, who are allowed to watch the spectacle

from nearby rooftops. Although visitors may make contributions to help with the

food, much of the cost is still borne by the villagers, who revere the cranes.

I, too, revere cranes. I can’t help feeling joy whenever I hear or see them, so I’ve been looking forward to this trip to Kichan for a long time. Lee and I saw a few Demoiselle Cranes in July, 2007, when we crossed Siberia and Mongolia on the Trans-Siberian Railway. That route took us through part of the summer range of the Demoiselles. Now and then, as the train zipped along, we glimpsed a pair of them, usually with a couple of half-grown chicks walking safely between their parents. Demoiselles are the smallest of the cranes, only about three feet tall and weighing 4-7 pounds, yet they migrate across the Himalayas to winter in the Indian subcontinent and then fly back across the mountains to breed. You can see their astonishing flight over the Himalayas in this video and one of the hazards they face on that journey in this clip from the BBC. |

| View Lee’s clip here to get an idea of what it was like to be standing on that rooftop looking out over the temple: |

|

I’d been surprised that no pigeons had discovered the grain, but they soon

did. Then we had the amusing sight of a cat among the pigeons, slinking along

trying to sneak up on them with no success at all. Eventually, it was scolded

by the householders and left the arena in disgrace. (This was actually the

first domestic cat we’ve seen in India.)

Soon after, a pair of Ruffs joined the pigeons, which was rather a surprise. (Ruffs are largish shorebirds whose males grow fantastic feather headdresses and neckpieces (“ruffs”) in various colors during breeding season, but the ones we saw today were in the cryptic plumage worn outside breeding season.) |

Cat among the Khichan Pigeons |

|

White-eared Bulbul |

Indian Silverbill (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons) |

|

The cranes kept accumulating in their staging areas but not daring to land in

the feeding area. They flew around and over us in great masses, seeming to

check us out. Our hypothesis was that they were spooked by having people on

two of the rooftops.

I was able to point out the arrival of the first crane in time for the others to see it land. It was a full adult, but we soon realized that it had an injured foot that wouldn’t support its weight. It hopped about using its wings for balance, obviously hungry enough to overcome its fear of humans. It was soon joined by a juvenile and another adult. I thought at first that these must also be especially hungry birds, but then I realized that they were probably the mate and the offspring of the injured bird. (One of the reasons cranes are so revered in folk cultures around the world is their fidelity to their families.) While skeins of cranes flew all around us and more flew in to land in the staging areas, those three fed in a far corner of the compound for half an hour or so until a child ran by along the fence, which scared them away. |

|

Crippled crane and juvenile (left) feeding |

While others circled low |

|

At last, three hours after we’d arrived, they suddenly began leaping over

the fence and flying in from the more distant staging areas. You can feel the

frenzy in Lee’s clip here:

(If you want to see more, this is a good close-up video of the cranes in one of the staging areas, and this nice slow-motion video will show you the grace with which they land in the feeding area.) |

| We spent another twenty minutes watching the feeding cranes until their compound was completely filled and the cranes were lined up along the swirls of the grain as though at troughs. It was a glorious sight. When something alarmed them, they all turned in that direction, the black-and-white of their heads making a striking pattern. I particularly enjoyed getting a close look at the males, who are larger and brighter than the females and have quite massive gorgets of black feathers. |

|

Happy cranes |

Handsome cranes |

|

We finally left Khichan, reluctantly and much later than we had expected. While

we were boarding the bus, skinny little boys gathered around to ask us for pens

for their school and toffee for themselves, neither of which we had to give

them, unfortunately.

The return journey allowed us to see more of the countryside. It was mostly arid, goat-shriveled desert with hard-scrabble farms full of poor people working, as everywhere, terribly hard. |

|

|

|

| The bus stopped at one point so we could see a pair of Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse (which are easily identified by the fact that they have no chestnut on their bellies). I could see them well from my seat, which was good, because (having had a rather nasty episode of arrhythmia while we were on the roof in Khichan) I found myself to be much too wobbly to get out to go for a walk with the others. (Don’t worry, it happens, and thanks go to Pat for sharing her water so I could take the necessary pill.) Lee did go on the walk and reported back that he had seen a Green Bee-eater, Isabelline and Desert Wheatears, and a Greater Short-toed Lark (I love that name), but no Indian Courser, which is the bird we are most hoping for. As the bus continued further, I did spot the Indian Roller that Dion called, a truly lovely lifebird. And we got our first Indian Hare. |

Indian Roller (Image courtesy of Amy Sheldon) |

Green Bee-Eater (Image courtesy of Amy Sheldon) |

Great Indian Bustard (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons) |

Well, actually, the Thar Desert bird we’d most like to see is the Great Indian Bustard, but since there are no more than 300 of them left on the planet, that is not likely, alas. (They were not long ago widespread throughout the subcontinent.) |

| Back at camp, I wanted nothing but sleep. Lee insisted on accompanying me back to our tent before going up to have lunch himself and decided to stay with me rather than going out for the three-hour desert drive that started at 4. Amy returned from that with some excellent photos of exciting birds: |

Southern Grey Shrike (Image courtesy of Amy Sheldon) |

White-eyed Buzzard (Image courtesy of Amy Sheldon) |

|

When Lee got back from dinner, he reported that they’d sat outside to

watch a local band and dancer for half an hour before going up to do the

checklist and eat dinner. I was sorry to hear that the group still hadn’t

gotten an Indian Courser, though they did get some very good birds. Our

marching orders are to be packed and at breakfast by 7 tomorrow, so I’ve

set the alarm for 6. Tomorrow night, we will be on a train!

My birds for the day: |

| Grey Francolin | Indian Peafowl | Demoiselle Crane | Ruff | Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse |

| Rock Pigeon | Eurasian Collared-Dove | Laughing Dove | Little Swift | Indian Roller |

| House Crow | White-eared Bulbul | Indian Robin | Purple Sunbird | House Sparrow |

| Indian Silverbill |

Sandhill Crane ice-skating near Princeton (2001) |

A few more thoughts on cranes, because they’re on my mind:

Humans have long been fascinated by cranes. The Ramayana tells of a female crane crying in grief after her mate is killed by a hunter. The name here for the Demoiselles is derived from the Sanskrit word “kraunch”, which is a cognate for “crane”, derived from the same proto-Indo-European word (though old sources in English more often speak of eating cranes than of eulogizing them). At the Slimbridge Wetland Centre in Gloucestershire (which is trying to reintroduce the Common Crane into Britain), Lee and I once saw a reproduction of an evocative archaeological find, side-by-side fossilized footprints of a crane and a human child imprinted on a British mudbank 7000 years ago. There was also a map of the British placenames (towns, villages, and fields) that incorporate “crane” (in Old English, Old Norse, or Cornish), which demonstrated that cranes must once have been distributed over the eastern half and far south of the island. But cranes were extinct in Britain by the 17th Century. I know of no mention of them in Shakespeare and only one in Chaucer (“The crane, the giant, with his trumpet soun’”). We were in Hungary a decade ago for fall migration of Common Cranes, but the only gathering of cranes we’ve witnessed larger than the one today was along the Platte River in Nebraska during spring migration of Sandhill Cranes, where the birds number in the hundreds of thousands for a few weeks each year. The sound of those multitudes was overwhelming. We have also managed to see a few of the painfully rare Whooping Cranes (in Florida), which leads me to recommend this amazing short video of a pair of Whooping Cranes dancing with a pair of Sandhill Cranes. |

| Oh, and don’t miss this video of a pair of Common Cranes at Slimbridge defending their tiny chicks from a fox. It makes me hope that Britain might really have cranes again someday. |